You see this figure a lot when you start reading about cancer: About 78% of all malignant disease is diagnosed in people 55 years or older. (American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2010) For that reason alone one would expect to find fewer cases in earlier centuries, a point I made in my recent Times story. By examining skeletons from the days of the Neanderthals through the year zero (when B.C. became A.D.) anthropologists have calculated that the mean lifespan was 30 years with a maximum of about 45. I read that in an interesting new book, How It Ends: From You to the Universe by Chris Impey, a professor of astronomy at the University of Arizona. (The book is not only about human longevity but also the longevity of the universe, a dizzying sweep across subjects. So far I’m up to page 50.)

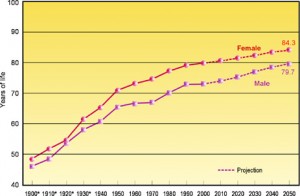

The same low life expectancy continued through the Renaissance, Dr. Impe writes, except for royalty who could expect to live until 50. (Reading that brought to mind the autopsy of the mummy of Ferrante I of Aragon, the 15th century King of Naples, who died at 63 apparently from metastatic colon cancer.) It has been only in the last two centuries that lifespan has been increasing. By 1900 the rest of us (at least in the developed world) had caught up with Renaissance kings and queens: Children born in 1900 could expect to die at 50. For those born in 2000 life expectancy is 80.

All that was mostly familiar but Dr. Impey surprised me with this observation: almost all of the gain in lifespan came from a reduction in childhood mortality. “In other words it’s a myth,” he wrote, “that our ancestors endured lives that English philosopher Thomas Hobbes had labeled ‘nasty, brutish, and short.'”

Now I’m not sure what to think. If an abundance of infant deaths, through accident or infanticide, dragged down the average life span, then a significant number of people who survived childbirth might have lived well past 50. If so that would cast some doubt on the assertion that old age is the predominant reason there is more cancer today. What we need to know is the median, not the mean. More things I need to sort out.

I have been grappling all week with the issue of longevity as I try to finish a draft of my third chapter, which concentrates on ancient cancer. Archaeologists of the future exhuming a 21st century graveyard will surely find more cancer than in, say, a medieval crypt. But some scholars like Luigi L. Capasso, an Italian anthropologist, have argued that the discrepancy cannot be explained entirely by our living longer. He points to “the very strange fact that an increase in cancer prevalence has also been noted in countries in which life expectancy was minimal in the past century.” (Capasso, L. L. (2005), Antiquity of Cancer. International Journal of Cancer, 113: 2–13). I just read in the CIA World Fact Book that life expectancy at birth ranges from 38.48 (so precise!) in Angola to 89.78 in Monaco.

But isn’t there an easy rebuttal to Dr. Capasso’s argument? These countries would also be the ones with poorer nutrition, higher rates of chronic infection, and rising tobacco use. More people in the third world, mostly children, die from diarrhea than people die from cancer in the developed world. (That is also from the Impe book.) In poor countries now undergoing rapid development there will be increased urbanization, with more chances of spreading human papilloma virus and hepatitis, which are associated with cervical and liver cancers. If medical care in these countries is improving (from abysmal to mediocre) more cancer might be detected and better records kept. Some of the rise would be an illusion. As the country grows more prosperous people will be slowly adopting the lifestyles of the industrialized world, gaining weight (obesity is strongly linked with cancer incidence) and longer lifespans.

Dr. Capasso’s implication is that there is more cancer today because of industrial carcinogens. So many friends I talk to take that for granted. Until recently I would have too. But the deeper I dig, the less evidence there seems to be. It is all so much more complicated.

5 Comments

I had heard that Xenophon (a contemporary of Socrates) had lived into his nineties, but the wikipedia article puts his age in the mid-seventies. I was curious about the monarch question in particular, since it seemed like we should already have fairly good records readily available about that (to the extent that they exist at all). Looking at a short list of French monarchs starting from around 400 AD (Chlodio-Childeric, just from the wikipedia articles, so caveat emptor and all that) We have three monarchs who live past fifty (56, 62, and 64 years of age), six monarchs who live past 40 but not fifty, and three monarchs who do not make it past 40 (37, 16 and 16). There were a couple entries that did not provide age data (presumably there was none) at all. Obviously it’s not a representative sample, and I can’t vouch for the data, but if a quarter of a population of French monarchs spanning between 392 and 721 lived into their sixties, then it seems unlikely that 50 years of age describes the probable limit of human mortality at this time.

Very interesting post. I’ve never heard that the increase in life expectancy is due predominantly to a decrease in infant mortality.

In addition to the increasing prevalence of environmental toxins, another idea occurs to me. Perhaps the r…eduction of infant mortality has released the evolutionary pressure on cancer prevention. For example, more people are near-sighted now than they were 1000 years ago not (just) because our lifestyle causes myopia but because the invention of eyeglasses allowed the otherwise blind to survive and reproduce. Similarly, it is possible that the same childhood ailments (or genotypes susceptible to those childhood ailments) are associated with increased propensities for cancer.

That’s my hypothesis of the moment, anyway :)

I recently heard something similar in bemoaning that Social Security going broke because everyone is living “so much” longer. Turns out the SSA tracks this information and if you made it to 65 in 1940 you might make it another 13-14 years and if you make it to 65 today you have only 15-17 more years to live (on average, of course, for men).

I think short-sightedness is a problem of a piece with cancer. How do we know there weren’t just as many cases of myopia back in the day? I don’t understand why people just assume everyone had great eyesight until humanity started being coddled by effective medical treatment. The case for maladaption is both weak and seems to come from nowhere.

There tend to be two contradictory, mutually held and widespread beliefs about humans before industrialization-one, that everyone was healthier, because of all that exercise, fresh air, and natural selection, the other that lives were brutish and short because they didn’t have modern medicine and indoor plumbing.

I assume that recent increases in average lifespan (which seem to be well documented enough) really are probably due to the better nutrition and less stressful environments of modern life. But if that’s true, then it doesn’t seem unreasonable to suppose that something close to contemporary lifespans were possible for those of our ancestors who were lucky enough to live in conditions that nearly approximated ours. It just happens those conditions were rarer, and so fewer people enjoyed their benefits.

If we had better data on the percentage of people who died in their sleep after living long lives, we could get some sense regarding what the optimal lifespans were before the 20th century. But I suspect getting information like that is going to be a real pain in the butt.

I know it is not very glamorous or intellectually stimulating, but our increase in life expectancy and improved health came from better sanitation, improved housing and nutrition.