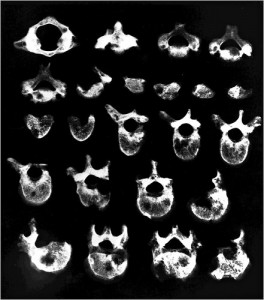

From A. Sefcakova, et. al., "Case of Metastatic Carcinoma From End of the 8th to Early 9th Century Slovakia"

On the Tuesday between Christmas and New Years, my story Unearthing Prehistoric Tumors was published on the cover of Science Times, the weekly science section of the New York Times. The subject was the antiquity of cancer, which has probably existed since the first multicellular creatures slithered on earth. (The picture on the right is an x-ray image of vertebrae from a medieval human skeleton marked with signs of metastatic carcinoma, a cancer that arises in the soft tissues of the body and migrates to bone.)

“Cancer is an inevitability the moment you create complex multicellular organisms and give the individual cells the license to proliferate,” Bob Weinberg, a prominent cancer researcher, told me when I met him last fall at the Whitehead Institute in Cambridge, Mass. “It is simply a consequence of increasing entropy, increasing disorder.” He is the co-author of The Hallmarks of Cancer, one of the most influential papers in the field. It describes in fascinating detail the multi-step process through which a single cell becomes malignant. (It is available as a pdf.)

I first came across Dr. Weinberg in a book by my colleague Natalie Angier, Natural Obsessions: Striving to Unlock the Deepest Secrets of the Cancer Cell. I read it when it was published in 1988, shortly after I had taken a job at the Times. The office where I worked (the Week in Review) was directly across the hall from the Book Review, and one of the editors there asked me to do a brief telephone interview with Natalie, who was teaching at the NYU Graduate School of Journalism. It wasn’t necessarily expected that I read her whole book, but once I started I was hooked.

More recently I have been reading Dr. Weinberg’s own popular works: The Renegade Cell and Racing to the Beginning of the Road. He is a good, clear writer, a talent that also shows in his recent textbook, The Biology of Cancer.

In fact I have already acquired enough cancer books to fill a rolling library cart. I have two of these now and use them to create small pockets of order in an office that is otherwise buried in books. A folder on my computer (361 megabytes so far) is stuffed with notes, drafts, downloaded papers, et cetera — material for a book I am writing about the science of cancer. If all goes well it will be published in a couple of years by Knopf in the United States, Bodley Head in England, and whoever buys the foreign translation rights.

For almost two years after the publication of my last book, The Ten Most Beautiful Experiments, I tried to decide what to take on next. Most of what I have written — in books and in articles for the Times, Scientific American, Slate, and other publications — has been about the physical sciences, but I wanted to immerse myself in something entirely new. As I go along I’ll be spinning off more Times stories about the surprising things I am learning. So much of what I thought I knew about cancer is turning out to be wrong.

I am also toying with the idea of charting my progress with this journal. I have mixed feelings. A while ago in The Santa Fe Review, I wrote about my aversion to blogging (please see My Anti-Blog). I was an early adopter of the Internet. Since the mid 1990s I have had my own Web site, coded entirely by hand, describing my books and providing biographical information and links to my newspaper and magazine stories. But that is more or less static with only an occasional update. Again, maybe it is time to try something new.

George Johnson

talaya.net

6 Comments

Glad you took the plunge. Can’t wait to read.

Thank you for the welcome. “The Stoichiometric Equivalent” looks great. There is too little good writing about chemistry.

Great to see you on the full-fledged, comment-enabled blogosphere, George! I look forward to reading this. (Right now I am listening to you, so I will have to postpone commenting on your debut post.)

Much appreciated, and thanks for listening to the blogging heads of Science Saturday.

I don’t have access to the peer reviewed paleontology articles, but unless there is objective evidence that a bone lesion is a cancer metastasis, you cannot say that a bone abnormality, even in radiological images, is caused by metastatic disease:

http://www.google.com/search?q=bone+lesions+that+mimic+metastasis&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official&client=firefox-a#hl=en&sugexp=ldymls&xhr=t&q=Ct+scan+bone+lesions+that+mimic+metastasis&cp=8&qe=Q3Qgc2NhbiBib25lIGxlc2lvbnMgdGhhdCBtaW1pYyBtZXRhc3Rhc2lz&qesig=hvtdIOh_nA3Y1FA3nmDwiw&pkc=AFgZ2tlT8FEHDherIo_KQU7HPCz2u-eggOohgh7lrEFaOCqpGqHv0cpgRTVkXqhlrfkvrTwvAOBtgODimP9BqJou5EopmsiilQ&pf=p&sclient=psy&client=firefox-a&hs=Q7D&rls=org.mozilla:en-US%3Aofficial&aq=f&aqi=&aql=&oq=Ct+scan+bone+lesions+that+mimic+metastasis&pbx=1&fp=241062ed1d424d73

It is a fascinating body of literature. The authors offer corroborating evidence like the nature of the lesion: whether it is osteolytic, eating into the bone, or osteoblastic, adding bone tissue. And they consider the pattern of the spread and discuss alternative diagnoses like osteomyelitis and osteoporosis. In a few cases like that of the Scythian king more sophisticated tests are performed like the one for prostate-specific antigen.