Last night I was up until 2 a.m. working on my third chapter. This morning I finally cleared the decks enough to dig into the problem posed in my previous post about ancient life spans and cancer:

If an abundance of infant deaths, through accident or infanticide, dragged down the average life span, then a significant number of people who survived childbirth might have lived well past 50. If so that would cast some doubt on the assertion that old age is the predominant reason there is more cancer today.

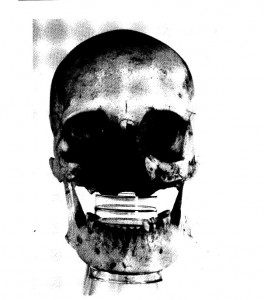

The skull of an ancient Egyptian woman whose face was eaten off by cancer. From Eugen Strouhal, “Ancient Egyptian Case of Carcinoma”

That raises the bigger question of how mortality rates are estimated for the centuries before census records were kept. It turns out that whole books have been written on the subject, paleodemography, in which the age of old skeletons is gauged by their physical appearance. That data is then fed into a statistical model. A very good paper on this is W. J. MacLennan and W. I. Sellers, “Aging Through the Ages,” Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh (1999) vol. 29, pp. 71-75. It is clear from the paper that child skeletons are included in the count, so it seems that the mathematical analyses would have to allow for that. (I’ve sent out a couple of queries to clarify the point.) I also wonder how often the bodies of infants (especially those murdered by their parents) were buried in cemeteries, allowing them into the calculations.

MacLennan and Sellers cite another paper, “Length of Life in the Ancient World: a Controlled Study,” in which J.D. Montague of Charing Cross Hospital estimated the median age of death (not the mean) for a sample of Greek and Roman men born before 100 B.C. He excluded not only those who died during childhood but also from acts of violence. “A study of these survivors would supply more information about genetic and constitutional influences on health than the mortality of the total population,” he wrote. “A murdered man has nothing to say on this score.”

I was startled by his conclusion: these survivors typically lived to about age 70. But his methodology seems questionable: his study was based on 298 people prominent enough to be included in the Oxford Classical Dictionary.

More still to sort out.

One Comment

Suits my prejudices. Obviously there is selection bias, but that’s what we’re looking for, right? If you’re trying to figure out how long a person might live under optimal conditions, then people prominent enough to be listed in the Oxford Classical Dictionary constitute a good sample. Data on peasants might be more representative (and obviously this is important for speculation about age-related cancer incidence in the ancient world), but I don’t see that there’s a big difference from being murdered and being worked to death.